Uccello, Correggio, Tiepolo

Some proposed forebears of a new aesthetics

What might a new aesthetics consist of in the visual arts? What follows is something of an answer.

First though, it would be shoddy of me not to gesture briefly at what the question sets aside, that minor matter of why it is any major aesthetic of endurance—an artistic movement or style characterizing a class of artworks that speak for their own time but are not reducible to it (in the social, psychological, and technological terms that cultural products may be reduced to or explained by); and that are not confined to their time in their ability to carry meaning but speak for themselves, with voices heard differently yet nevertheless heard down through the centuries; and that have consequences for art’s history, refracting the light we see the “existing monuments” of the past in, and consequences most importantly for art’s future, opening new corridors of formal and expressive possibility—why it is such an aesthetic, the new, ever arises.

If a reason can be given, in the cleanest possible language it was given by implication in a statement Martin Gurri made the other month: “A new aesthetics requires a new metaphysics.” To me this is incontrovertible. Social, psychological, and technological change, together and apart, are insufficient causes of aesthetic revolution, these domains too narrow to influence anything more than trends or experimental blips in art. Transformations across these domains have washed over us for a generation! And a major artistic movement has not automatically followed.

For a new art to flourish, the metaphysical system woven among it need not be organized, nor thrashed out in public, nor broadly subscribed to, nor particularly consistent. Through their works and their professed ideas and beliefs, artists within the same aesthetic movement have always given differing, incompatible, and contradictory answers to the major questions goading them. What they have tended to agree on, rather than answers, are the all-consuming questions themselves—their substance and unabating significance.

If I had to guess—and this is the kind of speculation we are free to make and should—I would say that artists working in a recognizable new aesthetic register will concern themselves variously with how the universe is more than a naturalistic system; with the layered nature of reality; with those aspects of embodiment that data cannot touch; with the soul as mortal or immortal; with the soul’s relation to matter, particularly the tactile matter we call visual art; with where a hard new line between private and public should be drawn; with art as a nonpersonal practice; with how the body is not a prison; with the possibility for certainty that makes uncertainty consequential; and with the good that is pleasure.

None of this is to say that art is a pure product of a metaphysics. Artists, not the nebulous belief systems they subscribe to or invent, create artworks. Here is one way among many, though perhaps the primary way, in which art and mass culture are distinct: The minimalist grayscale living and retail space materialized unbidden out of the present era’s ethos of sterile efficiency and end-of-history longings. The same unbidden occurring never happens with art.

I leave further aside how it’s all the other way around in the case of masterpieces—artworks that do not present or illustrate a certain understanding of reality but originate a new understanding.

My book on the Muses I’m hoping will do its part in all this and is entirely about art’s history, and existing works of art (individual paintings, compositions, novels, sculptures, poems), and not all these grim and bothersome abstractions.

Whether ours is a time of great freedoms or great conventions in art depends on whom you ask. Giving an overview of the state of contemporary art is not my remit here; artistic practices are so heterogeneous that summaries tend to say a lot of nothing, but allow me to make a few points.

By now it should be obvious that the supposed break from history1 occasioned by contemporary art never happened. Conceptualism is of course now an historical movement, though its strategies are deployed in much contemporary art that forgets, doesn’t care, or never knew its procedures are fifty+ years old. The post-historical period in which aesthetics become what only theory can determine has turned out to be another period in history, another finite chapter in the narrative that gets tiresome at times but never ends. In this chapter it is simply pluralism and open-ended inquiry instead of a distinct aesthetic vocabulary that are burning out in imaginative exhaustion.

The art market can be squarely blamed for the faux-modernist, novelty-for-novelty’s-sake logic that has prevailed in contemporary art for decades. But anyone who feels art has reached an impasse has to look beyond the corrupting influence of undiscerning capital and see how artists’ relation to history—whether they create in the illiterate zone of believing the past never happened, or whether they take up history as their subject and material—is why this chapter is ending so vapidly.

Historicism and citation (art about history, employing appropriation, quotation, direct critique, reenactment, or research-based and archival practices) are the long-established modes for contemporary artists to make use of the past, more often than not as a means of commenting on the present. The less dedicated sprinkle historical references into their artist statements in a transparent attempt at lending gravitas to the enterprise. Studied types treat history as an external resource to be mined.

The choice to recognize art’s history as a live chain of influence and elected inheritance was never not available. It can be made by whomever, whenever. My view is that artists working in a new aesthetic, seeing the past in art as more likely than the present to point to the future, will make that choice.

A new aesthetics will be cool, sexy, and soaring or will never transpire. Three artists who should be forebears of a new art: Uccello, Correggio, Tiepolo.

If you were Lorenzo de’ Medici and the opportunity arose for you to forcibly seize Paolo Uccello’s San Romano battle paintings from the palace home of the family that had commissioned them, you would take them for yourself as he did. The three panels, now at the Uffizi, the Louvre, and the National Gallery in London, are the painter’s great works, as magnetic as anything in art.

Their weirdness doesn’t diminish, no matter how well you know them. Take the London painting: Why this pink carpet-like ground with its broken breadstick lances? The pasted-on carousel horses? Why the military leader Niccolò da Tolentino’s unfeasible, spectacular red-wool-and-gold-thread turban? And the huge abundant oranges, glowing with life in a battlefield. Across the panel, a horizontal band of baby blue, made brighter by the horses’ gold insignias, stands out above the pink earth. Who is fighting whom, exactly?

It’s the early Renaissance; Uccello is modeling his figures geometrically with spheres and cylinders. Fifty years later, observing from nature and allowing for classical idealization, Raphael and Leonardo will depict horses with an anatomical accuracy not seen in art since antiquity, if ever. Looking at them now, their illusionism (the horses’ realistically tensed muscles, their violent twisting, the truer shading) feels in no way like an improvement on Uccello’s taut, iconic forms.

The artist’s obsessive experimentation with linear perspective, that new invention, is evident in each panel, in the grids the broken lances on the ground make, the foreshortening of figures and armor. Despite the backgrounds in the London and Uffizi paintings, where soldiers fight on the distant rolling hills, any depth here cannot begin to forsake or compromise the paintings’ flatness, their end-to-end saturation with shape, their insistence on form that isn’t a Gothic insistence but what looks to our eye like a Modernist one. It’s no wonder Barnett Newman found the sensation and the logic of his own aesthetic in these works, painted half a millennium before abstract expressionism.2

The paintings give meaning back to the hollowed-out word “design.”3 Every angle of the raised lances matters. Mixed in among flat, unbroken passages of paint, detail and pattern are engrossing. All colours and tones communicate, together and apart, even with the losses sustained through damage and age (notably, all the soldiers’ armor, which has oxidized to gray, was originally gleaming silver leaf).

Like Botticelli, Uccello isn’t lost in the liminal transition phase between major aesthetic periods but stands prominent. Neither earlier Gothic nor later Renaissance artists achieved the charismatic graphic quality for which we know them both. The determining factor in Uccello is that he is himself completely. His mathematics never made him cold or mechanical, rather it made his art into something the opposite of generic—more individual, and therefore intimate. Self-determining, or put another way, self-pleasing, doing only his own weird thing, Uccello made in these works some of the coolest paintings of all time.

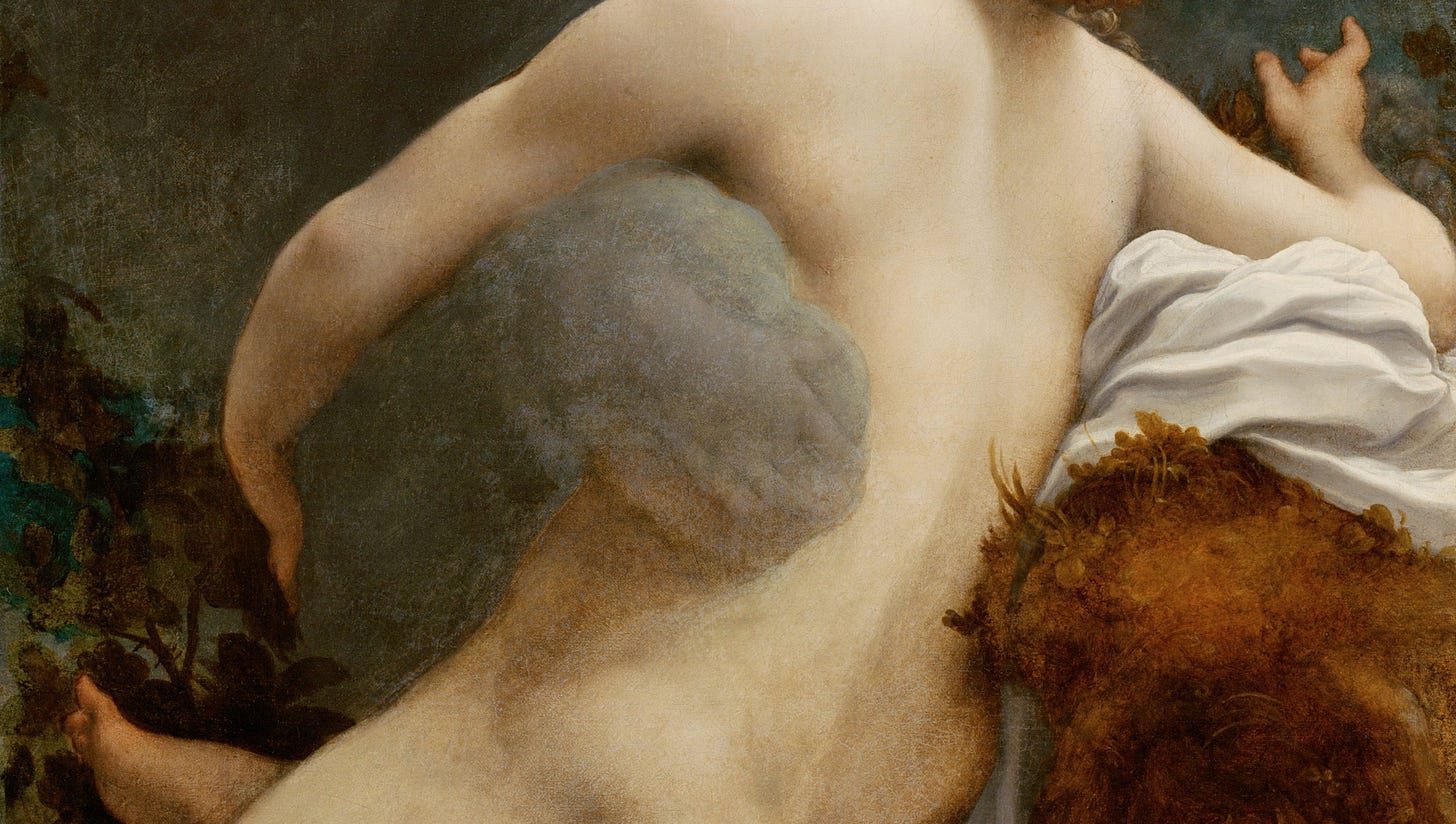

Correggio’s sexiness certainly had not been achieved in painting before him and would not be repeated until perhaps Velázquez more than a hundred years later.

It’s inconceivable he found the trace of this quality elsewhere and developed it, either consciously or unconsciously, let alone learned it in another master’s workshop. Correggio’s mythological nudes4 are all different women in different situations, but not one has any of the kind of ceremony about her that you find in Titian’s beguiling goddesses, and that’s present in even the most frolicking nude by Rubens, whose love for the female form was devotional. Correggio’s lack of ceremony is what makes his nudes, the “sacred” as well as the “profane,” so gorgeous.

More specifically, their state of ease—complete abandon in Io’s case—is a function of their faces, postures, and settings when coupled with the painter’s technique, his unequalled rendering of light (warm moon-like light) on skin that makes them appear luminous and yet somehow not illuminated. His sfumato is as fine as Giorgione’s or Leonardo’s—more fine, since it is more suitable to Correggio’s subjects.

The collapse of private into public, public into private that we’ve lived through over the last thirty years, accelerating in the past decade, has to be undone in the future, for reasons that are evident throughout society. New art will relate or perhaps even mark those lines redefining the two realms for us. Correggio is the prime example from art’s history of how it can be done. The universe of difference between private show and public display is realized in his mythological paintings.

After Correggio we can skip the Baroque,5 go straight to Italian Rococo.

If Tiepolo is mere decoration, life in an undecorated world may not be worth living. His art proves, contra moralists from Plato to Adolf Loos, that sumptuous visual experience can issue from and appeal to the intellect, and Tiepolo’s is an operatic intelligence. The wonder of his works today is that this opera-like art remains spectacular without descending into kitsch. If kitsch, which so much contemporary art monumentalizes, has a chance of being excised from art in the future, we might consider how Tiepolo did it.

Compare his grand frescoes on ceilings and walls to others of the period and you can see that no other painter orchestrates both an ensemble cast and the spaces between them—whether ethereal clouds or pure light—with his delicacy and daring. In addition to the frescoes are certain large allegorical paintings on canvas6 that in content and form are similarly celestial.

Renaissance perspective was above all rational and bounded. Tiepolo, painting two centuries later, took three-dimensional illusion to an untethered extreme, ruining our earthbound sense of space, velocity, and direction. Space does not vanish to a point but curves in, blows itself open. Tiepolo treats us to the experience of being surrounded by divine activity, gods solid and weightless, ourselves simultaneously beneath and behind and around them. We might be another tumbling putto or lesser deity, soaring and ascending as we look on.

The artist understood people’s love for fat baby thighs and haughty beautiful women, and he understood colour at its most recklessly attractive. The scale of his subjects in these works—myth, epic, the triumph of empire, glorification of his patrons—allowed for an unembarrassed theatricality impossible to imagine today. Return to anything like this style of ceiling painting cannot happen. What our time shares with his art is a heightened self-consciousness—a state we’re burdened with for as long as digital surveillance and photography dominate society. Tiepolo, on the other hand, gives us self-consciousness without a trace of anxiety, and no art than his could appear less encumbered.

My concern here has been with paint, as that’s where my allegiance lies. I’ve no expectation that the great paintings of the near future will necessarily be figurative; the last century’s masterpieces were more often abstract than not.7 Painting will be at the heart of visual artistic practices for as long as we live between walls.

I opened here with the question of what a new aesthetics would “consist of,” not “look like.” It’s not my intention to say the vocabularies or styles of these very different painters will be taken up in the future, or ought to be. I simply hold that certain elements of each artist’s aesthetic register—their impact—not only call to us today but are moreover those elements thus far unexhausted in art.

The story told: Institutions beginning with the pharaohs concerned themselves with identifying and upholding what they deemed to be supreme works of art, but the forms those artworks took (statues, paintings, relief sculpture) were not really theirs to decide: Tradition, craft knowledge, and inherited hierarchies of form established which specific classes of objects were “art.” Conceptualism, beginning with Duchamp and then properly in the 1960s, took that “specific classes of objects” to be an invented constraint and did away with it. Since then contemporary artists have been free to do and to make what they want, unbound by the precedents of medium and craft, and the authority previously retained by tradition has in a weird way been handed over to the institutions (today, the galleries, biennales, schools, periodicals, and art market), which now have this double mandate of deciding which artworks are good, and moreover deciding—by way of theoretical and philosophical arguments—what counts as an artwork in the first place. The result of this new state of pluralism is an end to art’s continuous historical trajectory, wherein forms and aesthetics developed one from the next. Supposedly, freedom from history’s constraints has allowed artists to create more vital and important works, in more forms than ever, guided by convictions that are self-made, uninherited. I recount this story as someone who loves Duchamp, from the crafted objects and the paintings to the installations and the readymades, and who thinks having contempt for him is about the most disqualifying opinion on art a person can have—but knowing Duchamp’s brilliance is not the same as endorsing every work of concept-driven performance, installation, video, and digital art that follows as art deserving of the name, let alone as valuable. I would not go so far as to think of Duchamp’s as a terminal aesthetic, the first and last possible of its kind, like for altogether different reasons an artist’s such as William Blake’s is, though I’m sometimes inclined to.

Compare with a slightly later battle painting by Piero della Francesca, a scene just as emphatically horizontal. Or Vasari’s battle frescoes at the Palazzo Vecchio, painted more than a century later. Claustrophobic, busy, detailed, forgettable: no design.

I’ll be commencing my book project on these paintings later in the year when I complete the Muses book.

Everything important about the Baroque, Correggio captures nearly a century ahead of time. Drama and sensuality, emotion and dynamism, grandeur and the immediate: All are there in the Parma Cathedral dome fresco, the Notte, TheMartyrdom of Four Saints (a full hundred years before Bernini), and the nudes. Probably Baroque proper is the language of photography and film now, not paint.

Three major oil-on-canvas paintings in this style are at the Met, Norton Simon, and London’s National Gallery. Dozens of oil sketches, made in preparation for the frescoes and considered completed works in their own right, are in major European and US collections. Future artists should study the oil sketches even more closely than the frescoes.

Critics who say painting has always been an abstract art (formal elements upon a flat surface) may well be right; those who say all paintings are representational (because referential or revelatory) might be, too. I doubt, however, whether it’s fruitful for painters to share this ambivalence.

Probing, perceptive argument that needs rereading and reflection. Sidebar: Are Sean Scully’s paintings contemporary extensions of Tiepolo? I’ve seen many Tiepolo works in situ but few of Scully’s, so I’m not sure. Wayne Thiebaud’s luscious paintings of banal objects, of which I’ve seen many, may also fit with Tiepolo.

This is a wonderful essay that offers a compelling diagnosis of the ailments of contemporary art while pointing towards a path forward. It is convincing (and a very pleasurable read) because it is rooted in an evident love of painting, and avoids sterile “theorizing.” I look forward to reading your book on the Muses.