Muse among the Drafts: Part I

The unforgettable in art

Saint Sebastian by Sandro Botticelli is the first superlative nude in the history of Western painting.1 No male figure in art could be said to be more beautiful than Botticelli’s saint. His beauty is haunting—which is to say, he is more than beautiful. An artwork may be supremely beautiful and utterly forgettable. What is it about this painting that is haunting?

It was hung on January 10, the saint’s feast day, 1474, inside the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Florence, a short walk from the neighbourhood where Botticelli was born, died, was buried, and, not counting his year in Rome painting the walls of the Sistine Chapel, lived his entire life. Its subject was immensely popular in art throughout Europe at the time. Legend held that Sebastian, a praetorian guard in the Roman army, was sentenced by Diocletian to death by arrow-fire for his faith and conversion of soldiers and prisoners under his watch. The saint’s cult arose in the fourth century; he would come to be worshipped as a protector against the plague. By the time of Botticelli’s commission, veneration of the saint was at its peak. Thousands of Sebastians would be painted for churches and chapels over the next two centuries.

A hundred years earlier, a new altarpiece at Florence Cathedral depicted the saint surrounded by archers, his body—wretchedly, though hardly realistically—pierced all over with arrows. Artists by this time were portraying Sebastian nude and at the scene of his martyrdom, but the impersonality of the medieval saint lingers into the fourteenth century.2 In the Early Renaissance, Botticelli’s elders typically represent Sebastian accepting his persecution willfully or passively. He gazes attentively up at the Lord in the large left panel of Piero’s Misericordia polyptych; in a fresco by Gozzoli—painted, though only nine years before Botticelli’s work, in an altogether late-Gothic style—he appears unbothered, as in a Crivelli altarpiece; appropriate to his figurine-like body is his stunned and distant expression in a triptych by the Bellinis.

Of course Sebastians of the Renaissance are classically beautiful: the god Apollo, after a long millennium, returned. The saint’s physique and face now take on differing characters. Typically he looks heavenward, whether in contemplation (Perugino), wistfulness (Antonello), or longing (Leonardo); in suffering (Mantegna’s Vienna and Louvre Sebastians) or dreadful supplication (Signorelli, Pollaiuolo brothers, Il Sodoma). Otherwise he looks off elsewhere3—his bearing one of terrible sadness, in Foppa; of heroic struggle, in Titian; of resignation, in Durer; but also, conversely, of innocent and elegant indifference in paintings by Cima.4 During the Counter-Reformation, worshippers become newly intimate with Sebastian, who suffers now in a state of ecstasy. He is defiant in a late Titian, wholly transcendent in a Tanzio. The fact of his being tied up becomes the pretext for sensational displays of the male body in works by El Greco, Rubens, and Reni.5

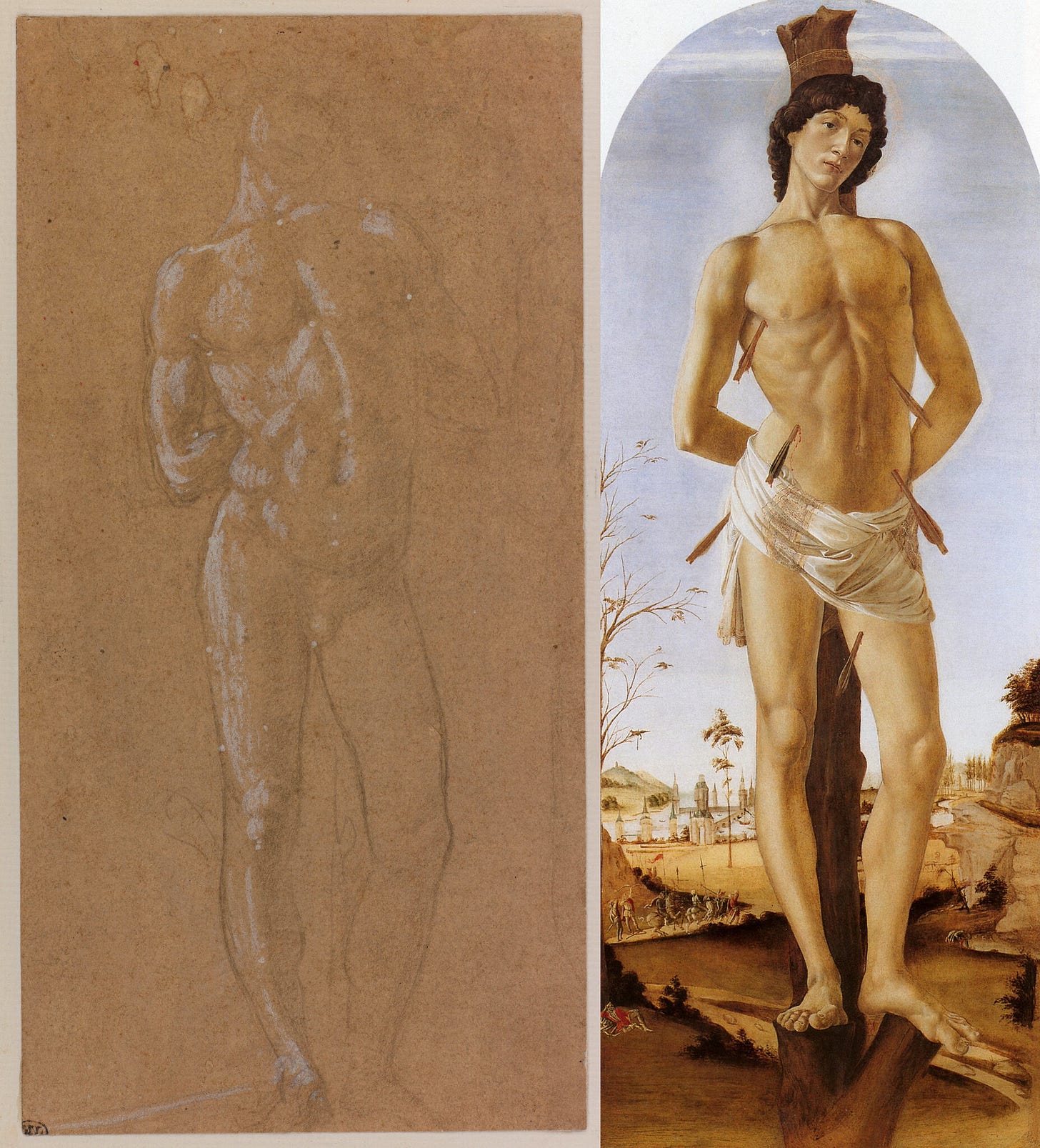

Botticelli’s saint has a quality none of these paintings share. Compared with the one-man melodramas of the Baroque, his Sebastian should appear sedate. Instead, after those he strikes us only more intensely. Comparison with other paintings shows mainly what he is not. What is that unforgettable quality in him? The question we should be asking is, What hand did the Muse have in Saint Sebastian? Botticelli’s drawing made in preparation for the painting reveals it. Looking between the artist’s draft and his completed work, we see exactly how the Muse guided Sandro Botticelli.

The study is on a sheet roughly 20 centimetres long, a tenth the size of the two-metre-tall painting. Different attributions for the drawing were proposed in the twentieth century; it was long thought to have been copied from Saint Sebastian and was recognized only recently as a preparatory study by the artist.6 To render the figure’s anatomy, Botticelli has used two materials and techniques: metalpoint, for outlining the body’s contours, and white-gouache shading, for its muscular definition. Light strikes from the left, accentuating the torso’s vertical plane. You could mistake it for a drawing after a lost Greek bronze.

Saint Sebastian has a sculptural character owing to this same gorgeous interplay of lighting and physique. What the painting does not share with the drawing is the charge of the earlier figure’s pose. From the hips down, their forms are similar. Above the hips, the drawn figure—unlike the painted—is straining, possibly in pain. His wrists are held higher against his back, with radiating effects: The arms bend more, the back arches, the chest juts out, the muscles tense, the shoulders slant at an angle, and the whole body adopts a pronounced contrapposto. Absent any details showing the figure as bound and wounded, the pose is almost exhibitionistic.

Here is where the Muse intervened.

Everything about Botticelli’s Sebastian depends on his stance not being one of physical tension. Unlike almost every Saint Sebastian of the Renaissance and Baroque, he looks out at us directly. There is no shame in his face—nor is there humility, provocation, yearning, or pride. Imagine, now, that cocked head on the posturing body of the drawing. His whole demeanor would shift: The heavy-lidded eyes and prominent jaw would appear conceited. That unreadable face we know, the face we cannot forget, would be suddenly legible: an audacious, proud face. Had the artist painted the saint’s upper body as he sketched it, Sebastian would be another man entirely. He would be posing before an audience. Like all posers, a desire for the viewer’s attention and approval would animate him.

The haunting figure of the painting does not perform for an imagined audience. It would never occur to Sebastian to wonder what we think of him. The Muse understood this—and under her direction, the artist diverged from the straining pose of his earlier study. For his gaze to hold us as it does, Sebastian could not be posturing. Only the noble body in repose could have been married to that face.7

On account of his classical beauty, Saint Sebastian has been called the first heir to Donatello’s bronze David, sculpted some thirty or forty years earlier.8 I believe the nudes are equals less because they share some uncommon measure of beauty, and both manifest a reverence for the human form not seen since antiquity, but more fundamentally because each is one of those inexplicable beings, in art as in life, that is the total embodiment of an attitude.

Botticelli’s Sebastian is the embodiment of self-possession. Every element of him communicates this. He has to look us in the eye. His expression, the Muse knew, must be permitted to convey nothing but that quiet, passionate confidence. He is not some Stoic who overcomes his suffering through calculated reason, and is not distractedly indifferent like the saints of Piero and Cima and Perugino. Rather, he is the supreme individual who takes no special interest in the self or the self’s suffering. No other figure in art is more at odds with our performative, traumatized time. Sebastian’s unforgettable attitude, transmitted to us through his face and comportment, is of complete self-possession, as like a god.

This is the first installment of a two-part essay. “Muse among the Drafts: Part II,” on Matisse, T. S. Eliot, and others, will post two weeks from today.

I’m turning on paid subscriptions should any of you wish to support my work monetarily. Who knows when the hell I’ll have a book. All essays on here will remain free to read.

Given that the written record tells how panel painting was the most highly regarded of all artforms in ancient Greece, doubtless artists of the time produced two-dimensional paintings of the human form as majestic as the nude sculptures, almost exclusively in marble, that have come down to us either in the original or in Roman copies. Thanks to the twin destructive forces of nature and the human character—from fires and floods; gravity and erosion; iconoclasm and ignorance; greed, war, and the bleaching sun—panel paintings, categorically, have not survived. The very few remaining frescoes cannot be considered representative of ancient Greek panel painting; Athenian red-figure vases, glorious though they are, are less relevant still. We can only speculate, dreamily, as to the aesthetic greatness those painters, like the sculptors of bronzes, achieved between the fifth and second centuries BC.

In frescoes and mosaics from the Early Middle Ages, the earliest known depictions of Sebastian, he is indistinguishable from other male figures but for labels identifying him. For hundreds of years he appears in church decorations clothed and bearded—not unlike the biblical figure David, who would be immortalized by Donatello and Michelangelo as a naked youth, though medieval artworks by convention show him as a king in robes and crown. Later in the medieval period, the circumstance of Sebastian’s martyrdom starts being alluded to in his imagery, in the form of arrows that he holds. Artists by the fourteenth century almost exclusively depict him at the scene of his persecution. For more history, see Irving L. Zupnick’s Saint Sebastian in Art and Sheila Barker’s “The Making of a Plague Saint.”

In a handful of paintings besides Botticelli’s, the saint looks straight out at the viewer. These works are almost entirely within the Northern European tradition: the Sebastians of Memling, rigid and expressionless; Baldung, strangely animated; and Holbein the Elder, sorrowful and meek.

Cima’s works are notable both because his Sebastians betray no discomfort and, more generally, because the context of the saint’s martyrdom has been stripped from each image. Did Diocletian’s archers not bother tying him to a post or tree before shooting their arrow or two? These Sebastians, more than those by other Renaissance artists, give the impression that the saint’s identity is purely incidental to the figure depicted. Cima has painted pretty male nudes, not Saint Sebastians.

This is the representation of Saint Sebastian taken up by gay artists and writers beginning in the nineteenth century with Oscar Wilde. Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian in Genoa—the one seen by Wilde in his early twenties and, in reproduction, by the young protagonist of Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask—is distinctive for the sweetness of the saint’s face, contrasting with his mature, muscular body. On its own, the face is that of a child looking up at his mother.

The painting is at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The drawing is in the Louvre collection and was recently exhibited at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Art historian Furio Rinaldi, who curated the landmark Botticelli Drawings show, has pointed to the figure study’s “spontaneity of execution, absence of pedantic detail, and creative variations on the [completed painting]” as evidence of its preparatory nature. Rinaldi estimates that fewer than thirty sheets of drawings by the artist survive.

Saint Sebastian was produced during the first phase of Botticelli’s independent career, perhaps a decade before his first mythological painting. The vast majority of his works had been of the Madonna and Child. Except for two portraits and his personification of Fortitude, completed in 1470 for the Palazzo Vecchio, all the paintings he made before Sebastian had biblical subjects. Sebastian’s noble solitariness is a quality that characterizes the artist’s later figures from classical mythology. Rinaldi has called Botticelli a “choreographic” painter—a term that encompasses his figures’ “elegant, balletic poses” and the dance-like arrangement of those figures within his compositions. I believe the analogy can be extended. Each of his mythological figures, and his Sebastian like them, seem to dance to music that he or she alone can hear. This solitary, glyphic nature of Botticelli’s figures is most apparent in his group paintings Primavera and Birth of Venus, works in part so compelling because the relation of parts to the harmonious whole—of figures to each other, the narrative, and the landscape—is so elusive. In both paintings, even his slim orange trees do not cohere into a grove—a true garden of the Hesperides—but remain a grouping of solitary trees.

Art historians from Kenneth Clark, in The Nude (1956), to Rinaldi, in the recent exhibition catalogue, have made this connection between the two Early Renaissance male nudes.

Thank you so much for yet another point of view of this extraordinary artist and subject. I’ve restored various renaissance art in Florence, and your essay has inspired me to look at pieces I have worked on differently — an art historian’s insight into aesthetics is different than an art conservator’s. I’ve written about some of my restoration experiences in my substack “Over the Tuscan Dirt” if you’re interested. Thanks for sharing your insight.

Thank you for this beautiful gift of a post. 🙏🏻