Questions on the Beautiful

By Eugène Delacroix, the first and last painter, now in English

If one painter could replace another in the popular imagination, for the sake of the arts and for society it should be a Frenchman for a Hollander, both of the nineteenth century—Eugène Delacroix for Vincent van Gogh. In Delacroix (1798–1863) we have an artist who saw humanity in the uncompromising light of our immutable dual character, part animal, part divine. Civilization, Delacroix knew, was not a given, never guaranteed, and as both history and the newspapers showed then and still show, threats to civilization come not only from without. Delacroix refused to leave the eternally relevant subject of tyranny to political actors and historians, and so his paintings encompassed scenes from the present day and distant past, from North Africa and the Near East, from literature and myth.

These paintings tell us as much as the greatest volumes of fiction and philosophy can. To engage Delacroix’s great canvases [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] “requires an effort of will,” Kenneth Clark wrote, and the will to give one’s time and sustained attention, so one may begin taking from the insane riches offered by his pictorially maximalist paintings—their thrusting busyness, bodies and forms ambiguously related in space, colour and shape that enrich and further complicate those relations by conveying their own pulsing energies, the allover visible oil strokes carrying on a whole other plane the painter’s energy in applying them—is one part of this. We must look a long time. The other demand on our will is emotional. Delacroix asks—and we struggle with this more than audiences of his own time did—that we have the openness and fortitude to engage the dark heart of nature, including human nature, without the promise of catharsis. If his most violent paintings are theatrical, and dare us not to take pleasure in the theater, they are also devoid of irony, sentimentality, smugness.

The concept of social and technological progress was as alive in the artist’s day as it is in our own. For Delacroix, whereas the industrialists, the revolutionaries, and the bourgeoisie believed through progress man would overcome his bestial nature, he instead saw the march of progress as a descent into barbarism, that man’s cruelty and vulgarity were not being absolved, suppressed, or educated away but rather newly unleashed. It may seem strange to us that a person deeply ambivalent about, if not downright hostile to, social and technological progress was the most aesthetically forward-looking, critical, and experimental major artist of his time. Any seeming contradiction evaporates when we accept that banner terms like conservative or progressive do not transfer between the social and the aesthetic realms. In the latter realm in fact, in art, they are as good as useless—as Delacroix’s essay I’m introducing here proves.

Vanishingly few of history’s great visual artists are especially good writers. Delacroix is one of the handful of exceptions, an intellectual with the linguistic ability to externalize his thoughts in writing and a commitment to doing so, both in his private journals and essays he published regularly in French magazines beginning in the 1840s. In his journal we find Delacroix, as well-read as any visual artist ever, preoccupied over the course of his life with the different affordances of his medium versus the other art forms to which he was so dedicated, literature and music. What could painting do best, do at all, that novels and symphonies could not?

We are immensely fortunate to have the essay that follows, in which the last Old Master painter—and, equally, the painter who first anticipated modernism—takes up the matter of beauty, of an artist’s proper relation to the beautiful in art and to the past. Delacroix here is in his mid-fifties and a celebrated painter; he has gone from scandalizing at the Salon to being commissioned to paint ceilings at the Palais Bourbon and the Louvre, without ever compromising his vision. A decade from now the emperor will permit the display of paintings rejected by the Academy at the first Salon des Refusés, and in two decades’ time the Impressionists, indebted to Delacroix, will appall the art world and mount their own rival salons.

In 1854, the year this essay appeared, all this was yet to happen. What Delacroix delivers is a synthesis of truths he has known since he first became an artist and an art lover. Those who slavishly follow after the art of the ancients do not have the final say on the beautiful—they barely have a say at all. Delacroix is no aesthetic relativist: He emulated and adored the art of antiquity no less than his rival Neoclassicists did. The difference is that they misunderstood and sanitized the past, deriving from it false instructions that the ancients themselves never followed, making dead rubrics out of the vital classics. For evidence he draws from the greatest works in the Western tradition, from the Italian and Northern Renaissances, the Dutch Golden Age, the Baroque, all the while offering comparisons between the paintings that illuminate their varied inheritances from antiquity, the branching routes that beauty has taken since.

“Questions on the Beautiful,” which has never appeared before now in English, was published in the July 1854 issue of the Revue des deux mondes, a magazine to which Delacroix regularly contributed. Blake Bartlett, my husband and collaborator, and I are the translators. Together we are working on an English edition of Delacroix’s writings for Census Press. In the meantime, in the coming weeks I hope to publish a short series of close readings of paintings by the artist that can be seen in public collections. Also in the meantime I will share an update about my book on the Muses, which I’m halfway through writing.

For now the question: Have we the honesty, the fortitude, to love Delacroix?

—Alice Gribbin

Questions on the Beautiful

In the presence of a truly beautiful object, a secret instinct alerts us to its value and makes us admire it in spite of our prejudices or antipathies. That people of good faith agree about this proves that just as all men feel love, hate, and all the same kinds of passions, just as they can be drunk on the same pleasures or torn apart by the same suffering, so they are equally moved in the presence of the beautiful, as they are wounded by the sight of ugliness, of imperfection.

And yet it happens that when they have had time to gather themselves and reflect on their first impressions, whether by discourse or with pen in hand, these admirers, so unanimous one moment, no longer agree with each other, not even on the basic points of their admiration; the habits of school, the prejudices of education or nationality, overtake their spirits once again. Then it seems that the more competent the judges, the more disposed they are to contradiction; because people without such pretense either are weakly moved or hold tight to their admiration. We don’t include among these diverse categories the cohort of the envious, who always despair at the beautiful.

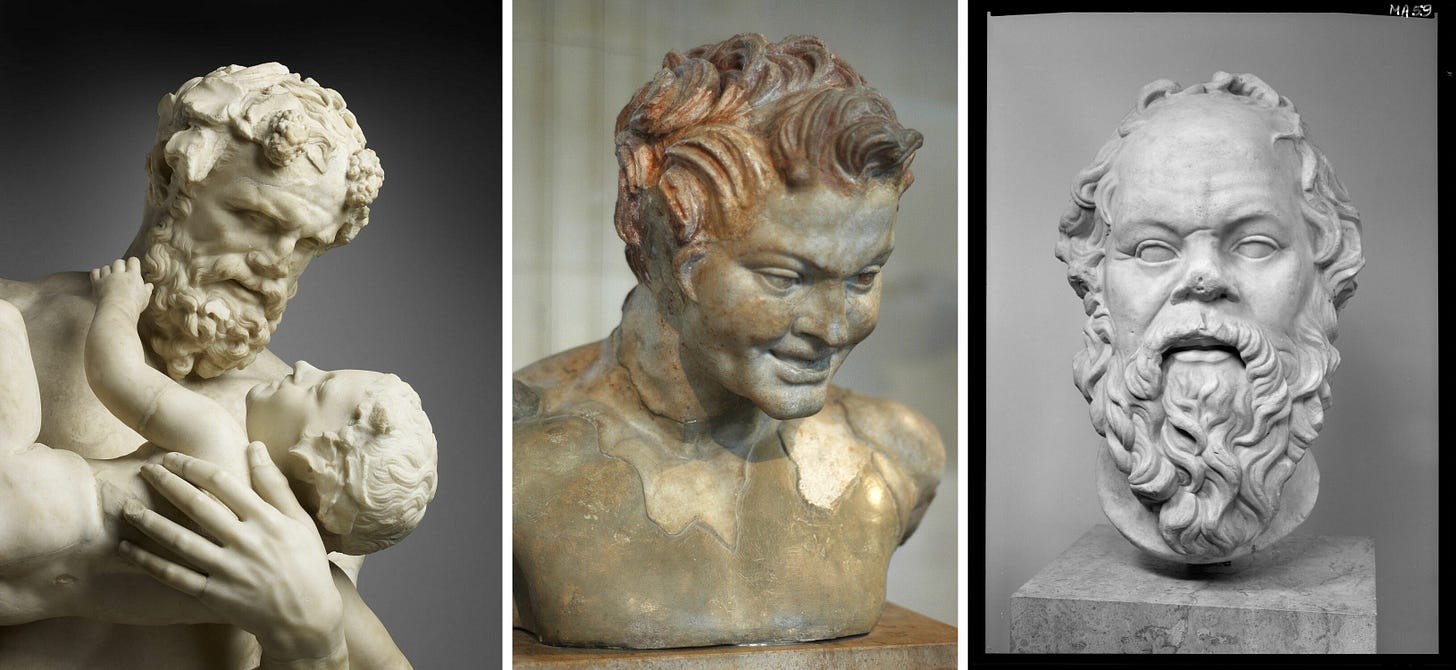

Is the sentiment of the beautiful what seizes us when we look indifferently at a painting by Raphael or Rembrandt, or a scene from Shakespeare or Corneille, and say: “How beautiful!” or is the feeling limited to our admiration for certain archetypes that define the beautiful? In a word, are the Antinous, the Venus, the Gladiator, and in general the pure models that connect us to the ancients the invariable rule, the canon from which we cannot depart under pain of falling into the monstrous? Do these models necessarily imply the idea of uniformity, along with the idea of grace, of life itself?

Antiquity has not transmitted only these archetypes to us. The Silenus is beautiful, the Faun is beautiful, even the Socrates is beautiful: This head is full of a certain beauty despite its little crushed nose, lippy mouth, and small eyes. It is not radiant, that’s true, with symmetry and the lovely proportions of its features, but it is animated by reflective thought and inner loftiness. The Silenus, the Faun, and so many other faces with character are ancient stone. We easily conceive how stone, bronze, and marble demand in the expression of some features a certain sobriety that is ugly and dry when imitated in painting. Painting distinguishes itself from sculpture through color, effect, and its accommodation of spontaneity, which allows for more exciting, less conventional details.

The modern schools have forbidden whatever deviates from antiquity’s authority. Even in embellishing the Faun and Silenus, in removing the wrinkles of age, in suppressing the inevitable disgraces, often those characteristics that bear the natural accidents and the work of representing the human form, the modern schools have naively shown that the beautiful for them is only a set of instructions. They have taught the beautiful as one teaches algebra, and not only that, but they also use facile examples. What could be simpler? To imitate all the characteristics of a unique model, to attenuate, to efface the profound differences in nature that separate the diverse temperaments and ages of man, to avoid complicated expressions or violent movements capable of disturbing the harmony of features or limbs—these are, in short, the principles that help one take the beautiful in hand! The beautiful is turned into a classroom exercise and made easily transmittable from one generation to the next, like a deposit.

Throughout history the sight of beautiful works proves that the beautiful is not met under such conditions; it is neither transmitted nor conferred like the inheritance of a farm; it is the fruit of inspiration’s perseverance, which can only follow stubborn labors; it comes from the gut with pain and thrashing, as with everything destined to live; it charms and consoles men and cannot be the fruit of a passing phase or a banal tradition. Vulgar laurels crown vulgar efforts. A fleeting delight accompanies works of caprice for the duration of their success, but the pursuit of glory demands other attempts: An endless battle wins one of glory’s smiles, and a small one at that. To get it, a thousand gifts and destiny’s blessing must reunite.

Simple tradition could never produce a work which makes one cry out: “How beautiful!” A genius sprung from the earth, an unknown and gifted man who abolishes the scaffolding of doctrines that the whole world rests on and that produces nothing. A Holbein, with his scrupulous imitation of his models’ wrinkles, who counts, in a manner of speaking, every hair on their heads; a Rembrandt, with his vulgar archetypes, full of such profound expression; these Germans and Italians of the primitive schools with their skinny and sinuous figures and their complete ignorance of the art of the ancients: All these sparkle with beauties and with the ideal that the schools seek with a measuring rod. Guided by naive inspiration, drawing from the nature around them, and doing so with profound sentiment, the inspiration that erudition cannot counterfeit, geniuses fill the crowd and cultivated men with passion. They express sentiments that are in all souls: They have found in their natures the priceless jewel that a useless science demands in vain from experience and from precepts.

Rubens saw Italy and the ancients; but, dominated by an instinct superior to all the exemplars, he returned from the place where beauty was born and stayed Flemish. He found the beauty of the people and the apostles, simple men, in the Miraculous Draught of Fishes, where he painted Christ saying to Simon: “Leave your nets there and follow me; I will make you fisher of men.” I don’t believe the Man-God said this to Raphael’s well-groomed disciples while granting them the institution. Without the admirable composition, without this clever positioning that puts Christ all alone on one side and the apostles arranged together facing him, and that puts Saint Peter on his knees receiving the keys, perhaps we would be shocked by a certain affectation in the poses and dispositions. Rubens, on the other hand, gives us broken and disjointed lines, inelegant and tossed about drapes, which blight the sublimity and simplicity of his characters: He is no longer beautiful in this respect.1

If we compare Raphael’s Disputation of the Holy Sacrament to Paolo Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana, in the first we find a harmony of lines, a grace of invention that is a pleasure for the eyes as for the spirit. However, the contrasting movements of the figures and the great care taken with forms in general give the composition a sort of coldness; these saints and Doctors seem not to know each other, and each of them seems to be frozen for eternity. In Veronese’s feast, I see men as I encounter them around me, varied faces and moods, conversing and exchanging ideas, the sanguine beside the bilious, the flirtatious beside the indifferent or distracted woman; in sum, life and movement. I do not speak of the air, the light, or the effects of color, which are incomparable.

Is the beautiful equally present in these two works? Yes, without a doubt, but in different ways: There are no differences of degree in the beautiful; only the manner of exciting the sentiment of the beautiful differs. The style of each painter is equally strong because it consists in a powerful originality. You can imitate certain tricks for portraying draped cloth and balancing the lines of a composition, you can seek the purest forms, and still you will not attain the charm and nobility of Raphael’s ideas; you can copy models with their lifelike details or studiously wrought illusions and still not encounter this life, this warmth, that is present everywhere and that forms the magic of The Wedding at Cana.

When David2 affirmed the liveliest admiration for Rubens’s Christ on the Cross, and in general for the most spirited paintings of this master, was it because of its resemblance to the paintings of antiquity, which he idolized?

Where does the charm of the Flemish landscape come from? What do the vigorous and surprising landscapes of Constable, the father of our landscape school and so remarkable in any context, have in common with the landscapes of Poussin? Doesn’t the search for style in the most conventional trees spoil Claude Lorrain’s a bit?

One remembers what Diderot said to the painter who made his father’s portrait, and who, instead of representing a simple man in his work clothes (he was a cutler), dressed him in his best clothes: “You have painted my Sunday father, and I wanted my everyday father.” Diderot’s painter is like almost all painters, who seem to believe that nature is wrong for making men as they are. They apply make-up, they Sunday their figures, and far from being everyday men, they are not even men: There is nothing under their curled wigs, their posed drapes. They are masks without spirit and without body.

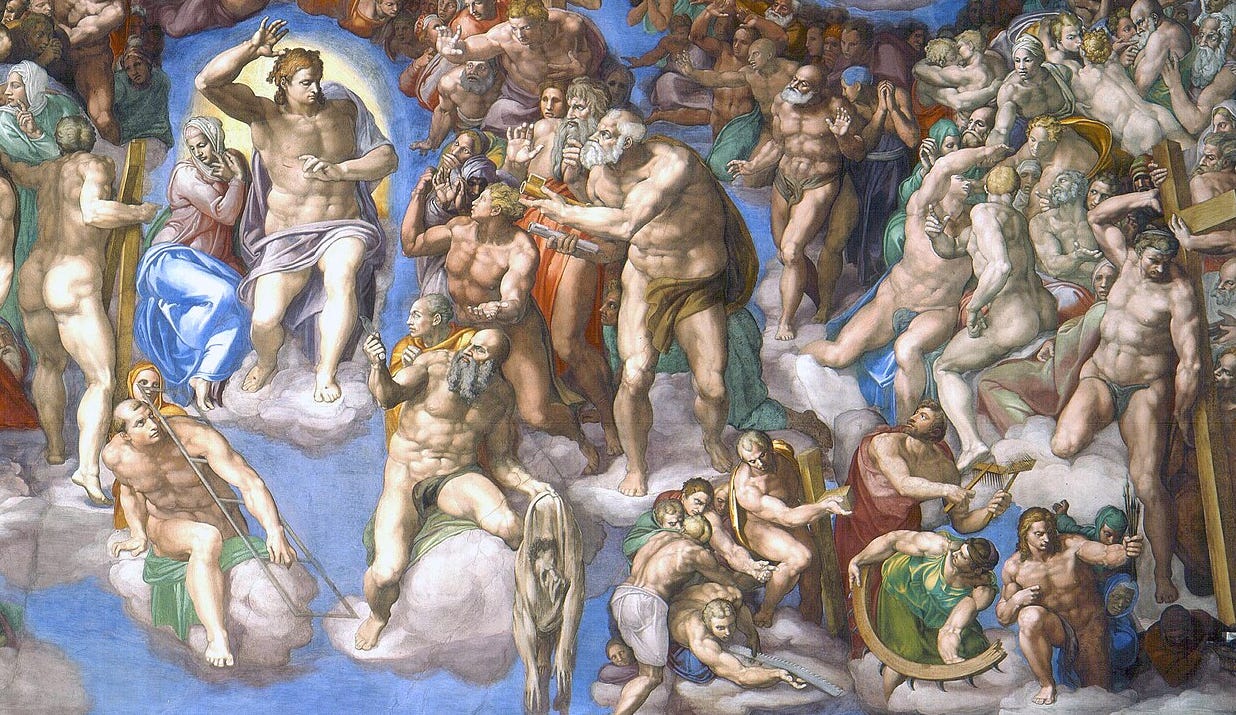

If the style of the ancients imposed the limit, if we only find the last word on art in absolute uniformity, how do we rank Michelangelo, with his bizarre concepts, tormented forms, outrageous or completely false geometries, which superficially imitate nature? You will be forced to say that he is sublime to excuse yourself from granting him beauty.

Michelangelo saw the statues from antiquity as we do; history tells us of the cult that he professed for these marvelous remains, and his admiration was ours; however, the sight of and esteem for these fragments changed nothing about his vocation or his nature; he did not cease to be himself, and his innovations should be admired alongside those of antiquity.

Among a master’s works, we observe that the most consistent are not always the most perfect. I cite Beethoven as a particularly good example. In his entire work, which seems to be only a long cry of pain, we notice three distinct phases. In the first, he strived to imitate the purest tradition: Besides imitating Mozart, who spoke the language of the gods, we already felt the breath, it is true, of melancholy, of passionate aspirations that at times betrayed his inner fire, like the whimpers of volcanoes between explosions; but as the abundance of his ideas pushed him to create unknown forms, he neglected correction and rigorous proportions. At the same time his sphere enlarged, and his talent reached its greatest power. I know well that the savants and the connoisseurs refuse to follow him through the last phase of his work: In the presence of these grandiose and singular productions, still obscure and perhaps destined to remain so forever, the artists, the professionals, are reluctant to see what must be gleaned from them; but if one remembers that the works of his second period, found inscrutable at first, have conquered public sentiment and are now regarded as masterworks, I will stand with him even against my own feelings, and I will believe, now, as many others do, that we must always bet on genius.

Critics do not always agree about the essential qualities that establish perfection. Those who are tempted to condemn Beethoven or Michelangelo today for not being uniform or pure would have absolved and praised them in other times, when other principles won the day. Thus, the schools have placed these principles at time in drawing, at times in color, at times in expression, at times—who would believe it?—in the absence of all color and expression. The English painters of the last century and the beginning of this one, an eminent school little appreciated in France, saw these essential qualities above all in the effects of shadow and light, as today we want to see these qualities only in contour, which is to say in the complete absence of effect.

It is permissible to think that the great artists of all time did not respect all these distinctions. Color and drawing being the necessary elements of their work, they didn’t strive to make one or the other predominate. Their own penchants led them to unknowingly emphasize some merits over others. Is it reasonable to think that a masterwork of painting might not present in some measure the reunion of this art’s essential qualities? Each of the great painters used color or drawing as his spirit deemed fit, which gave to his work this supreme quality the schools do not speak of, and which they cannot teach: the poetries of form and of color. It’s on this ground that they all meet, in all schools.

Before a morning landscape, bathed in dew, animated by birdsong, embellished with all the natural charms that touch the heart, the savant and the average man will think neither of line nor of chiaroscuro: They will be moved the same way, their senses will be penetrated by a hidden harmony, by this delectation that Poussin made the unique object of his paintings.

In his famous Painters Score Card, de Piles3 gravely reveals the different doses of color, chiaroscuro, and drawing that contribute to the talent of each celebrated artist. He does not give any of them a perfect score; the number 20 being regarded as the highest, he gives Raphael, for example, only an 18 for illustration, while Michelangelo earns a 19. On the other hand, Titian and Rubens, whom he scores liberally for their colors, present a considerable gap with respect to their drawings: He shows us the assets and liabilities of talents.

The amusing chemistry that analyzes great men! The precious discovery that they can be reconstituted to suit criticism; to take, for example, a part of a Michelangelo drawing that stifles with overabundance, in order to combine it with an unfortunate Rubens drowning in an excess of color! How the philosopher is chagrined to find Correggio’s contour perish in the chiaroscuro that envelops it and of which he is master; while Poussin, whose compositions burst with science that would suffice ten painters, is frighteningly short of chiaroscuro! The good de Piles appears convinced that with determination and some effort, each of these remarkable men could establish equilibrium between what he sees as their qualities, and according to him, if this equilibrium could be established, they would have come much closer to true beauty.

Nature has given each talent a particular talisman that I would compare to those inestimable metals alloyed with one thousand precious others, and that make sounds, both charming and terrible, according to the diverse proportions of the elements forming them. It is so with refined talents that cannot be easily satisfied. Attentive to captivating the spirit, they address it by all the means that art puts at their disposal: They revise a detail one hundred times, they sacrifice the brushstroke, studied execution, making the details emerge this or that much for the unity and profundity of the impression. Thus is Leonardo da Vinci, as is Titian. There are other talents, like Tintoretto, better still, like Rubens, and I prefer the latter because he goes further in expression; these artists let themselves be carried away by a sort of verve in their blood and hands. The force of certain strokes, to which they do not return, gives to these masters’ works an animation and vigor, which a more circumspect execution would not necessarily achieve. We must compare such effects to these singular sallies of orators who, carried away by their subject, by the moment, by the audience, rise to a height that overtakes their composure. We are satisfied with calling these particular flights that ravish the auditor and the orator improvisation. We easily conceive that in painting, no more than in the art of oratory, the kind of improvisation, if one wants to call it that, would only produce vulgar effects if these effects were not prepared and planned, in advance, by patient work, either through artistic practice in general, or with the material that is the orator’s or painter’s object. We typically pretend that effects of this kind do not bear scrutiny, like the effects produced by works with a more disciplined form. Mirabeau’s speeches, for example, do not answer, when one reads them, to the idea that his contemporaries have given us of their prodigious brilliance at the podium: Did they fall short of satisfying the condition of the beautiful when he delivered them, when he moved, mobilized, not only an assembly but an entire nation? Is it not possible that such speeches, widely read, even powerfully felt in the silence of the study, were received with cold approbation in the forum before thousands of listeners? Has a picture, so irreproachable in the studio, always fulfilled, on the great day of an exhibition, or when placed at the necessary height and in its own special place, the expectations of its admirers and the public?

We must see the beautiful where the artist intended to put it. Don’t ask the virgins of Murillo for the chaste unctuousness, the timid prudery, of Raphael’s virgins: Revel in the traits of their faces and their attitude of divine ecstasy, the persistent curse of a mortal creature elevated to unknown splendors. If either of these painters adds some of these legendary figures of pious worship or sainthood to pictures of the virgin in her glory, we are charmed in Raphael by their noble simplicity and the grace of their movements; in Murillo, we admire above all the expression of what infuses them. These monks, these anchorites that he shows us in the desert or in their cells, prostrate before the cross and thoroughly marked by pious practices, fill us in turn with a sentiment of abnegation and belief.

Is the beautiful absent in such penetrating compositions, which carry us to regions so different from those that surround us, which make us conceive the mortification of the senses, the power of sacrifice and contemplation, in the midst of our skepticism and the puerile distractions consuming our lives? And if the beautiful actually lives and breathes to a certain degree in these works, would they gain what they lack by resembling antiquity more?

We may wonder how the ancients got by without antiquity. Rembrandt, who was in a similar position, since he had never left the marshes of Holland, would have pointed to the mortar and pestle he used for preparing color pigments and said: Here is my antiquity.

We are correct to find that the imitation of antiquity can be excellent because we find there the observation of the laws that eternally regulate the arts, which is to say expression in just measure, the natural and its elevation altogether; what’s more, the practical means of execution are the most sensible, the most proper to produce the effect. These means can be employed for something besides the endless reproduction of the gods of Olympus, who are no longer our gods, and the heroes of antiquity. Rembrandt, in making the portrait of a beggar in rags, obeyed the same laws of taste as Phidias sculpting his Jupiter or his Athena. The great and necessary principles of unity and variety, of proportion and expression, is no less powerful in one or the other; only the qualities are encountered there in different degrees of excellence or inferiority because of the object represented, the particular temperament of the artist, and the predominating taste of the epoch.

We reproach Racine for having heroes that are not Greek and Roman heroes: I am tempted to congratulate him for it, and to be sure, he does not care. Shakespeare draws upon antiquity much more, whatever the classicists may say. His characters are modeled on Plutarch: His Coriolanus, his Anthony, his Cleopatra, his Brutus, and so many others are those of history, but this would hardly be a merit if the characters were not true; they are the men that Shakespeare wanted to paint, and they are the men that he and Racine have painted. What do I care that Burrus, Nero, Agrippa are from Tacitus? At the theatre, in an auditorium that doesn’t care about Tacitus or Plutarch, I want to see all their impassioned movements mingling with an interesting and poetic action that captivates me more than real history.

We have seen bizarre imitations at the theatre several times, where plays follow the great tragedies step by step; they were inspired by a certain color of primitive simplicity that is no longer a part of our customs and that leaves us cold. Tragedies made for the American savages would not have surprised us more. When an author of merit recently wanted to stage episodes from the Odyssey, he spoiled, to my mind, very interesting scenes, presented in beautiful verse, with misguided research on customs that baffle us. The swineherds of the divine Laertes astonished me more than they interested me; I would say as much of the curses that Odysseus and Telemachus address to Penelope’s suitors, and of the thousands of details of customs that can prick the curiosity in an original narration, but that ruin all action in the theater.

The ancients gave their plays choruses that were nothing but a personification of the audiences’ reasoning through what was being represented on stage. To our minds, the spectators extract the moral from what they see; they should make their own reflections on the fly, without additional reflections distracting them from the diverse events of the play and the developing characters. The Greeks became habituated to the choruses, which gave them transitions and a sense of what was to come. As a result, they were overly dependent on foregrounded effects that one can get from the play itself and the logical progression of scenes, a merit at which the moderns have excelled.

Fashion, which uses talent like a silk handkerchief and tells people what to think, has always provoked the question of the beautiful; fashion’s frivolous influence thinks it even extends to the immutable. Images of the beautiful are in the spirit of all men, and those who have yet to be born will recognize it by the same signs. Neither fashion nor books show us these signs: A beautiful action, a beautiful work responds in a flash to a faculty of the soul, the most noble one no doubt. A certain dose of culture can add something very fragile to the pleasure aroused by the beautiful, can unveil those obscure beauties hidden from the least experienced eyes; but this culture, often indiscreet, can also truly falsify judgment and mislead natural sentiment.

What! The beautiful, this need and pure satisfaction of our nature, flourishes only in the countries we romanticize, and we forbid ourselves to seek it around us! Greek beauty is the only beauty! Those who credit this blasphemy are men who do not feel beauty in any latitude, and who do not carry in them this internal echo that trembles in the presence of the beautiful and the grand. I don’t believe that God reserved for the Greeks alone to produce what we, the men of the north, must prefer; so much the worse for eyes and ears that are closed and for these connoisseurs who want neither to know nor, by consequence, to admire! This impossibility of admiration is in proportion to the impossibility of elevation. The elite intelligences have the task of reuniting, with their predilections, the different types of perfection between which the savants see nothing but abysses. Before a panel composed only of great men, disputes of this type would not last very long. I imagine the living lights of art reunited, these models of grace and power, this Raphael, this Titian, this Michelangelo, this Rubens, and their rivals—I imagine them reunited to classify talents and distribute glory, to those who have respectfully followed their traces, and to give one another the justice that centuries of appreciation have not refused them: They would arrive very quickly at their common mark, at this power of expressing the beautiful, but also of attaining it by different routes.

—Eugène Delacroix4

I.e., He is no longer beautiful in the way of the ancients.

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), foremost Neoclassical painter of the generation before Delacroix. Best known for The Death of Marat, Oath of the Horatii, and Napoleon Crossing the Alps.

Roger de Piles (1653–1709), art critic of the French Baroque period. Delacroix here refers to de Piles’s “Balance of Painters,” a table that appeared as the final section of his last published work, The Principles of Painting (1708). Read it here.

Essay originally published under the title “Questions sur le beau” in the July 15, 1854 issue of La Revue des deux mondes.

“[T]he beautiful. . .is neither transmitted nor conferred like the inheritance of a farm; it is the fruit of inspiration’s perseverance, which can only follow stubborn labors; it comes from the gut with pain and thrashing, as with everything destined to live; it charms and consoles men and cannot be the fruit of a passing phase or a banal tradition. Vulgar laurels crown vulgar efforts.”

Wow. Thank you for bringing this essay to our attention.

"Vanishingly few of history’s great visual artists are especially good writers."

I'm not sure what you meant by this claim. Michelangelo, Leonardo, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Bonnard, Rothko, Whistler are just a few names that immediately come to mind as excellent writers as well as artists. In fact the 20th century seems to have been awash with painters and sculptors who were eager to express in words their ideas and feelings about art, both their own and that of their contemporaries. Ben Shahn gave a series of lectures at Harvard collected as "The Shape of Content". I think we need to be careful when making sweeping generalizations like this.

In fact personal experience has taught me that some of the most skilled writers I know happen to also be visual artists. It's how they think.