A Supreme Fiction

On Coetzee's The Childhood of Jesus, briefly

The unappeal of op-ed writing is at least twofold. First, here is a writer who presupposes that her own opinion on events from only a moment ago, the circumstances of which she might have no broader understanding about, is so insightful as to be very interesting to strangers. Unless she writes with panache or is extraordinarily wise, hers is not a sensibility that appeals. Second, here is a written thing characterized by its very disposability. It is mass-market writing that expires upon being read.

I've no commentary to offer on the mess that was made two weeks ago at the National Gallery. But in room 43 of the museum that morning, in a voice posher than mine, a question rang out—a question so amazingly oblivious, on hearing it I was taken immediately out of the context of its utterance, and I thought instead about other matters, and that I might write on them, briefly.

“What is worth more, art or life?” To call absurd the dichotomy this question puts forth would be an affront to the glories of absurdism. Yet we recognize the dichotomy, which persists. We meet it in various forms, such as the idea of art (whether in the making or in the enjoying) as escapism. There is the world that we live in, with all its attendant troubles; then there’s this other place, where we can vacation for a stint—the world of art.

Last month I started and finished one novel, J. M. Coetzee’s The Childhood of Jesus (2013). Episodic and dialogue-heavy, the form of the book makes it appropriate for reading with a new baby in the home. A description of only what is strange about the novel would catalogue most of what it contains. The label “dystopian” or “speculative” fiction, however, does not adequately account for its strangeness.

There’s the time and place of the story, which do not map onto a time or place we know of. There’s the society our protagonist, Simón, finds himself in, in which a man can be safe, and treated well by others, and have his material needs largely met, and still feel dehumanized. Emotionally, carnally, Simón is ill-suited to this world, as most of us would be, ourselves.

There is the frustrating passivity of his peers. But then Simón’s own psyche is oddly stunted. He indicates little distress, and no pain, at having lost his former life. Hauntingly, he has the “memory of having a memory.” As the story progresses, his behaviour too becomes harder to understand. His actions and speech make a kind of logical sense to the reader—until they do not. The same is of course true of any well-established character in a novel: We feel a character is real when he is not always, or even often, entirely rational. But with such oscillations—passionate, reasonable, patient; irresponsible, indignant, resigned—Simón by the novel’s end seems entirely lacking a state of equilibrium.

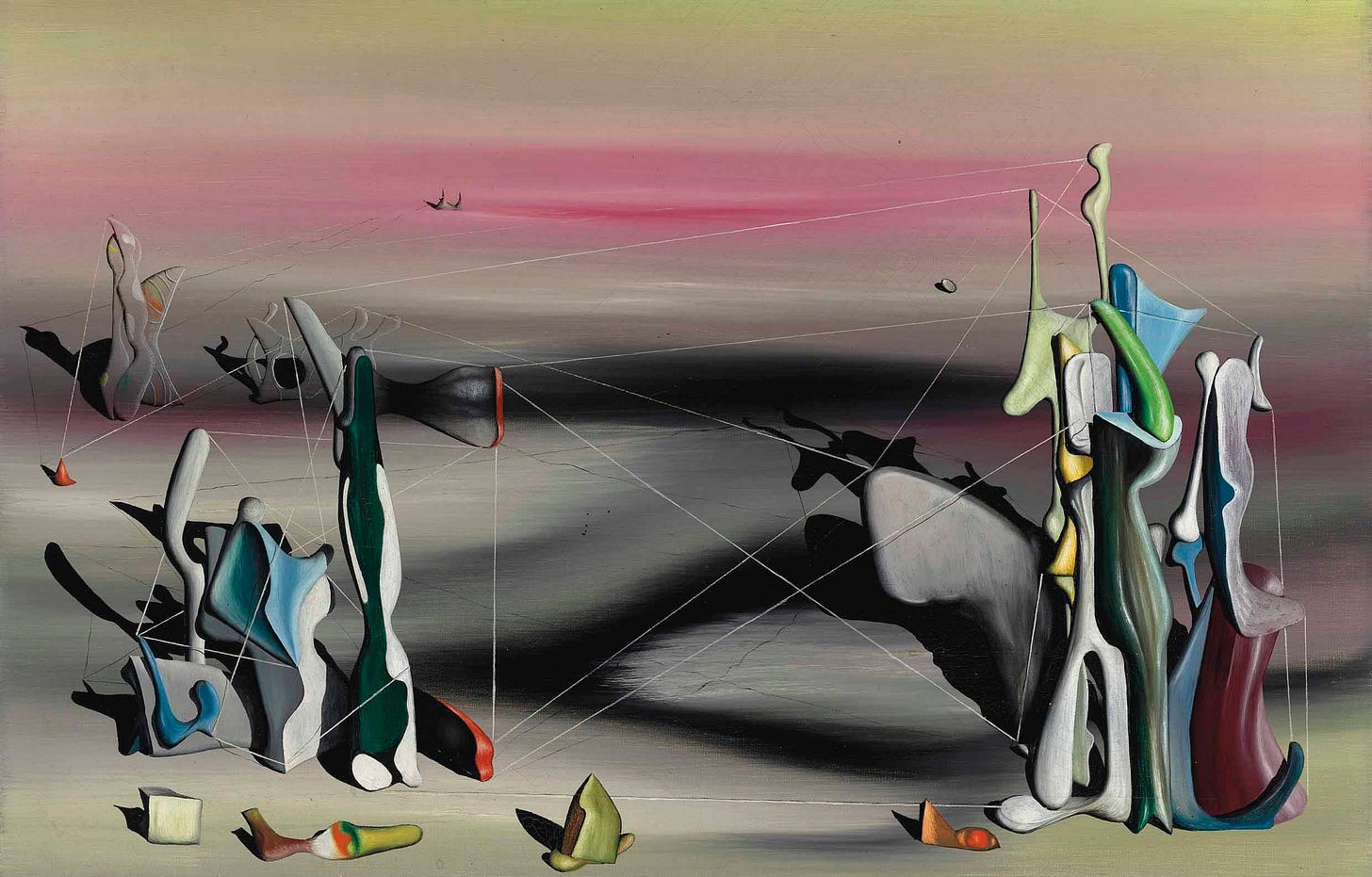

There is the staged, almost puppet-show, quality of every scene; Coetzee’s stringent prose; the explicitly philosophical content; the form of the Platonic dialogue that many conversations take. Work, relationships, sustenance, desire: All appear here in conversation not as the stuff of individuals’ lives, but as topics in the abstract, the nonstuff of metaphysics. It is why all the characters can be mildly infuriating. It’s also why, inevitably, the novel reads like an allegory.

But I don’t think it is one. The provocation of the title is insistent. The boy, David, like his ward Simón, proves to be a capricious character—on the one hand, ordinary and spoiled; on the other hand, brilliant. Whether or not David is divine seems to be a central question, and so every incident involving him in the book’s second half wants to be read as suggesting an answer.

What is the significance of the child’s attitude to mathematics, language, mortality, brotherhood? What does it all mean? And what is the novel saying about delusion, family, imagination, faith? What’s the broader meaning of all this?

While reading and on finishing The Childhood of Jesus, I felt a low hum of excitement and quietly frustrated. A week or two later, thinking back on the novel, my frustration had gone and I felt quietly thrilled. In this work so concerned with signification, with the gaps between words and ideas and the experiences and things to which they relate, my difficulty in knowing the significance of any one event or conversation to the wider story—my difficulty, put another way, in discerning the allegory—no longer bothered me. On reflection, it’s an artwork that helps me articulate for myself something difficult to express about being alive.

The ultimate strangeness of the novel is its indeterminacy. A reader cannot say what is and is not important in it. Besides all the talking, dramatic and consequential and sometimes implausible things happen. Yet on the scale of a character’s predicament, suffering a near-fatal workplace injury is not necessarily any more significant than one particular instance of unblocking a toilet.

Again, this is not undifferentiated writing. Mundane conversation follows the theoretical or profound. Quite bizarre and domestic events occur in turn. That which feels major or pivotal in the moment, in the reading—central to the novel’s meaning or allegory—really might not be. A small remark could be more important.

I’ve no interpretation of the novel to offer but instead the strange fact it held up to me about living: the fact that any moment’s significance doesn’t arrive then, with the moment. Whether something that happens or is said will echo through your life, accruing meaning and importance or simply remaining in memory, as that which can be revisited, be known again—whether a moment has significance is not, in the moment, yours to know.

Of all the forms and mediums of art, fiction is, for me, that which at its best brings my attention to the strangeness of living. I love many Modernist novels for this reason. The great invention of the stream-of-consciousness mode is that it captured in language the mind’s movement as it feels to have a mind and to be in the world, as one always is, going about one’s business. Stream of consciousness is the true form of realism in fiction.

I’m not putting forth any rules about great literature here, simply making observations. Just as a fictional work employing stream of consciousness may well be overblown, so the indeterminacy I’m ascribing to The Childhood of Jesus could, in a different writer’s hands, result in a tedious, underwritten novel. Specific evaluations of artworks (“this one work is extraordinary because”) are typically worthwhile; generic statements about art (“novels that do such and such succeed”) are always suspect.

Those aspects of Coetzee’s novel another reader might take issue with—its indeterminacy, its elusive allegory, its strangeness—for me are not faults, no more than Van Gogh’s all-too-excessive use of paint is in any way a fault.

Great, love this novel, as well as the next 2 in the series. Thank you for writing about it!

it would be strange to me if others do not find life strange...... I guess we need some thinking to wade through that.... as strange as it is....